Expecting the Unexpected: Finding Agency in Uncertain Times

What do you do when life takes an unexpected turn? Your answer may surprise you—mine did!

It’s been a while since I’ve written. I’m finally ready to tell you why.

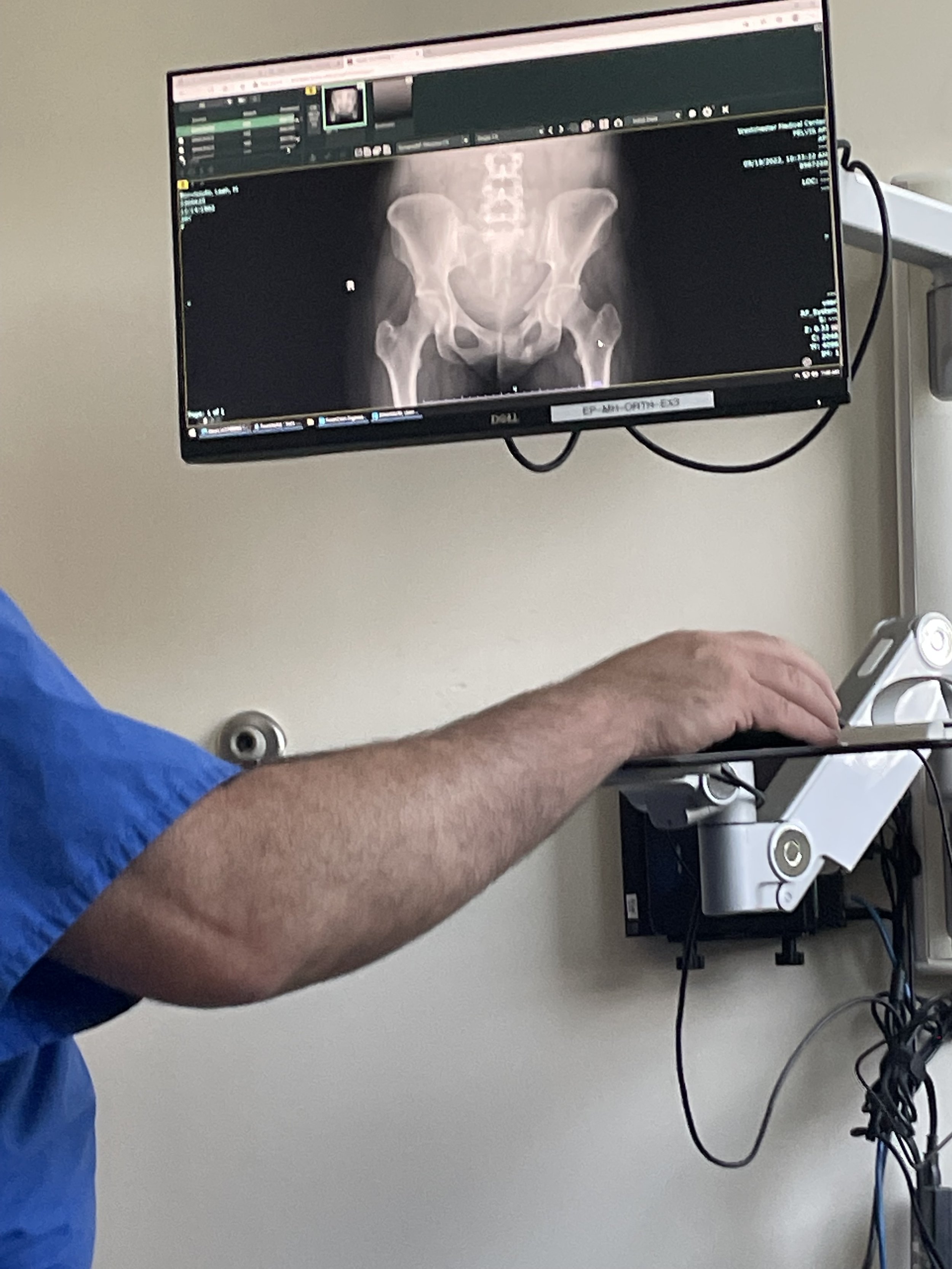

On July 1, I was in a car accident and broke my pelvis and sacrum.

It’s been my life’s work to help people prepare for unexpected moments. Helping people find clarity in confusion and trust in anxiety is the core of what I do. But nothing could have prepared me for the shock of this accident and the presence that it forced on me in the most unexpected way.

Today, I am walking unassisted. It’s hard and painful, but with enough focus, I can move my body by myself. There’s still a lot I can’t do. It turns out, rebuilding strength and mobility from the ground up is exhausting and confusing.

I’ve never had so much clarity about what I’m here to do and who I’m here to serve. For the first time in my life, my conviction is so much louder than my fear.

The Trickiness of Control and the Power of Choice

In my work, I talk about the power of choice, and how anxiety can take away our agency and ability to be present in the moment. There’s been so much that’s out of my control during this time that focusing on what I can control has been an effective distraction mechanism.

Immediately after the accident, I quickly realized how little I had control over anything. I also quickly realized: 1) how important it was for me to feel like I was in control, 2) how much I try to control everything in my life, and 3) how little control I actually had over ANYTHING in my life.

I realized fast that without structure—without a sense of control—my traumatized brain was just spinning and seeking blame. I quickly had to manually inject a sense of structure and control.

When I think back, this is how I’ve managed my anxiety for years. Instead of focusing on the things I can’t control (how I’m being perceived, social anxiety, etc.), I refocus my attention on something that makes me feel proactive and powerful—the structure and stability helps me feel in control so I can let go of overthinking and trust my gut.

The forced sense of control helped me focus on what I could control instead of everything I could not.

Choosing Gentle Focus and Living in the Breath

After the accident, I didn’t have full bodily control. I couldn’t urinate on my own for weeks. I could move with a walker, but even one step was immensely painful. My upper body was caving under the pressure of having to carry the weight of my whole body.

I will never forget a nurse named Laura who was with me for the first few days in the hospital. When I couldn’t move without excruciating pain, she explained why pelvic fractures were the most painful and the only thing that would mitigate the pain: Breath.

Turns out, I was holding my breath, something that was familiar to me in uncomfortable or unsafe moments.

Moving my attention to breath did what it does for me with anxiety—it created a Gentle Focus where suddenly I felt more in control.

It required all of my attention to minimize pain. There was no room for self-doubt, over-thinking, or getting distracted. And the gentleness was key.

In the past, getting to my breath had been a command, something I had to force. But after this injury, I can find that focus more easily, and being gentle with myself has been the only way to access it.

I didn’t always feel at home in my breath. If you’ve worked with me, you know that breath has become my escape key from my anxious mind. But it was always manual and took great effort to get there.

For decades before doing this work, I suffered from debilitating breath-based anxiety. I felt like a failure as a human because I couldn’t even do this one thing “right”.

But in the hospital after the accident, I knew how to find home inside my body, and it was in the breath. Breath was the only thing that was familiar. It was the only thing I could control. I knew how to use my breath to refocus my attention away from the pain.

I was never able to live in my breath with this much ease before. But now, it wasn’t a choice.

Gratitude Isn’t a Choice—It’s a Privilege

When people find out about my accident, they usually say something like, “That must’ve been awful,” but honestly, I’ve been filled with nothing but gratitude. The gratitude surprises and confuses folks! People applaud me for the “choice” of being grateful, but it hasn’t been a choice at all.

It’s been a privilege.

My privilege enables me to be grateful. The privilege of working for myself. The privilege of working remotely. The privilege of whiteness in an oppressive system that isn’t built to support the most underprivileged people. The privilege of having so much support from my partner and my friends.

When I woke up after the crash, covered in glass with airbags inflated all around me, I was flooded with gratefulness, even though it didn’t make sense.

I’m grateful that I didn’t need surgery and could start healing on day one.

I’m grateful that I was alone in the car, and that my kiddo wasn’t with me.

I’m grateful that I’ll recover fully, and that I’m already back to many of my daily activities (with a deep focus to minimize pain).

I’m grateful to Tim, my life partner, and many dear friends who came to care for me when I couldn’t do much for myself.

I’m grateful for Zoom and the ability to see clients remotely. I’m grateful for my clients, particularly those in healthcare, who checked in and helped me feel cared for, even in our sessions together.

I’m grateful to my best friend who just so happened to have had these same injuries. Her lived experience and advice got me through my earliest, scariest days.

I am grateful for the tools I’ve developed in this work that helped me focus in the midst of so much fear, pain, and trauma.

I’m grateful for cannabis, which created a buffer for the pain like bubble wrap, and was so much more effective than anything pushed and prescribed by the Medical-Industrial Complex.

I’m grateful that I don’t remember the accident at all. I’m hopeful the memories won’t flood back.

I still don’t understand the gratefulness, but I sure am grateful for it.

Managing Expectations—Expect the Unexpected

When working with people who have speaking anxiety, we work to expect the nerves (and trust that we know how to handle them when they inevitably come).

Sometimes, the surprise and shock is the hardest part to process. Expecting the unexpected can oddly give us a sense of control.

In the hospital, it took me days to start to relinquish control and to accept what had happened (still a work in progress and part of why I’m sharing here).

I didn’t share sooner because we live in a country that doesn’t support sick folks. I was scared that my business would shut down, something I couldn’t afford.

I also had so much support around me, and frankly, I didn’t think I could handle more of an influx of support. How grateful am I?

Throughout the past five months, every time I’ve been hard on myself, it’s been because of my own expectations. Why aren’t I healing fast enough? What if this pain lingers forever? I should be able to walk faster by now! Using Gentle Focus to rewrite my own expectations in the moment has been everything.

But managing other people’s expectations during this process has been trickier than managing my own.

Back when I took my first business trip following the accident, a cane clearly signified that I was injured. In an airport line, it was as if the seas parted and I was escorted through with ease.

It was immediately clear to me that this wouldn’t have happened if I wasn’t white, young, and privileged. It altered peoples’ expectations.

This week in the city, seeing clients for the first time in-person, I didn’t have a cane to signify my disability. I went up subway stairs one at a time and could feel the confusion. “Why aren’t they going faster?”

We’ve all been managing our expectations over these past few years. We’ve had too much practice managing disappointment, grief, shock, and a sudden, unexpected need for collective healing.

Trusting myself—and helping others trust themselves—has been my life’s work. Rebuilding my strength has been a matter of trust. Trust in my body, in my community, in my treaters—in myself.